I fought the urge to fill the quiet with reassurance. It wasn't the time for cheerful observations or gentle encouragement. Wes felt something locked away for over a decade, and my job wasn't to make it easier. I was only there as a witness.

"Funny thing about leaving. You tell yourself it's temporary. Just until things settle down and people forget." He set his foam coffee cup on the bench to his side. "Then, years pass, and you realize you're not the same person anymore. Maybe you never can be."

I reached out to touch Wes's thigh.

"Problem is," he continued, "you're not sure who you are instead."

A boat rounded the harbor mouth, heading out to sea. The captain must have been running late—most of the fleet was already out.

Wes turned to look at me like he saw me clearly for the first time that day. The careful distance he'd maintained since we'd left the ferry dissolved.

His voice was quiet. "Most people try to fill the silence. Patch things up. Make it tidy." He paused, then nodded toward the space between us. "You didn't. You just stayed."

The simplicity of his comments hit me hard. After years of isolation, every casual interaction we'd witnessed had been a small test of whether the world was safe enough to inhabit.

The day grew cooler, and I smelled wood smoke from chimneys already lit against the October chill. Somewhere nearby, a door chimed as someone entered a shop, followed by muffled voices and the shuffle of footsteps on worn wooden floors.

Wes breathed in deeply. Maybe this was the beginning of returning—not only to a place but to himself. To the man who'd once belonged somewhere and might, with time and patience, learn to belong again.

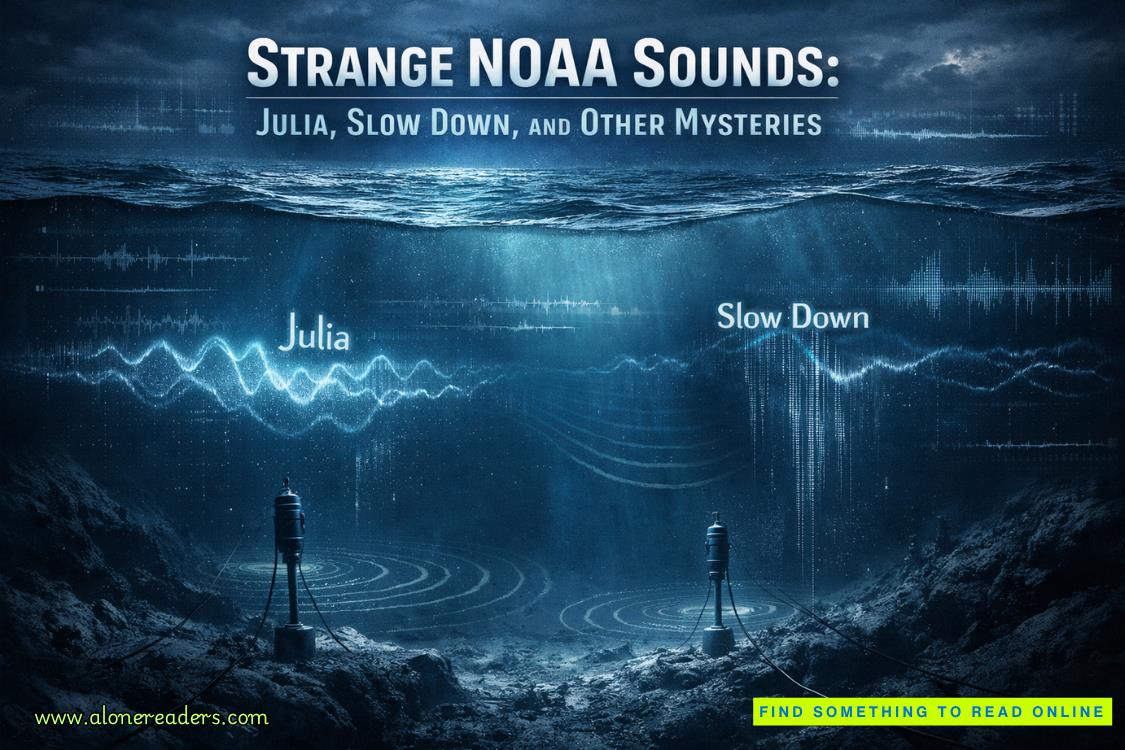

Beside me, his fingers twitched, and from somewhere out on the water, a buoy bell rang—soft and hollow—marking the moment like a heartbeat.

Chapter eighteen

Wes

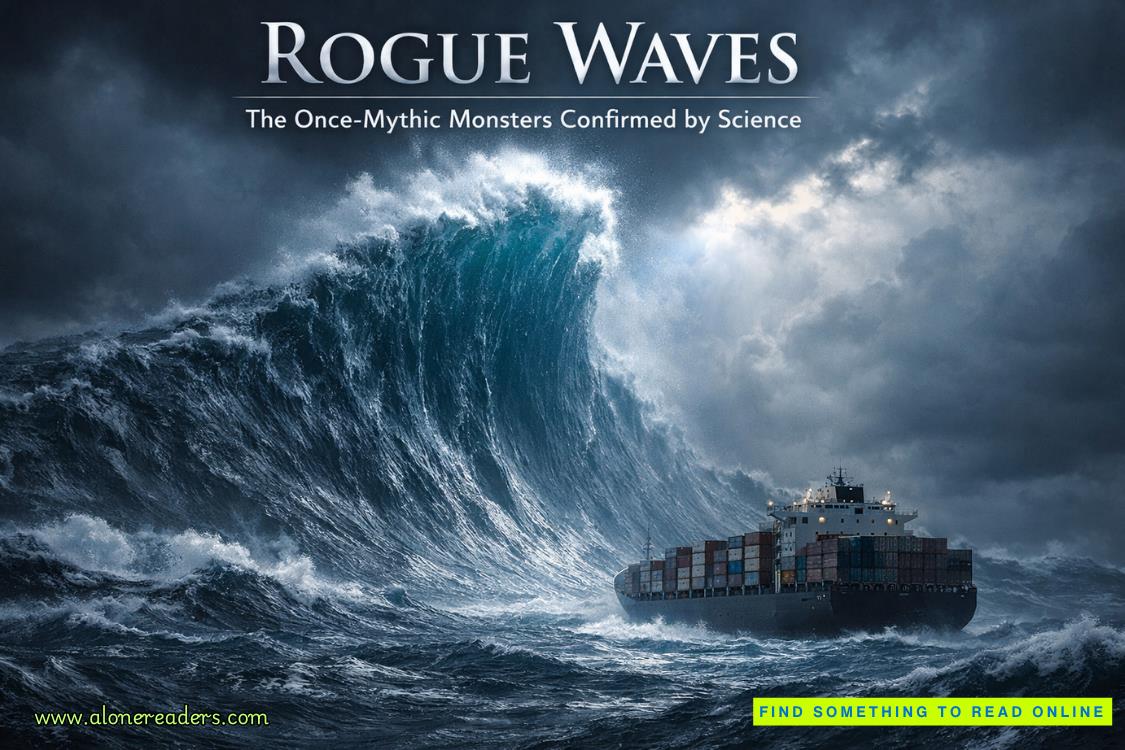

The water stretched smooth as hammered pewter between Whistleport and Ironhook, barely a ripple to disturb the reflection of clouds drifting overhead. October had settled into that deceptive calm between storms.

Chief Callahan's words from the video call still echoed—You don't owe me anything, Son—but it was the kids walking down the street who'd really rattled me. When I corrected his grip, that boy looked at me like I'd handed him something valuable instead of merely opening my mouth without thinking first.

It wasn't coaching, not really. It was remembering out loud.

I rubbed my thumb along the ferry's salt-crusted rail, feeling the rough texture against my skin. The boy's face when his skating suddenly clicked—pure joy, uncomplicated by the weight of expectation or the fear of disappointment. When was the last time I'd experienced anything that clean?

Eric shifted beside me, and I caught him watching my profile. He didn't ask what I was thinking about. Long ago, he figured out that direct questions usually sent me diving for cover.

When we approached the Ironhook harbor, Mrs. Pelletier stood at the edge of the dock like she'd been carved from the same ancient granite as the island itself. Her oilskin jacket caught the harbor breeze while a Red Sox cap shadowed her eyes.

She didn't wave or call out as the ferry bumped against the dock pilings. Instead, she watched us with the patient attention of someone who'd spent seventy-eight years reading the weather in people's faces. She'd planted her boots wide on the planks, ready for any disturbance.

"Didn't expect to see you two back so soon. Island miss you already?"

Eric shouldered his supply bag, grinning at her like she'd told him a particularly good joke. "You know how it is, Mrs. Pelletier. Civilization gets overwhelming after a couple of hours."

"Mm-hmm." Her watchful gaze turned to me. "Funny thing, though. I heard a whisper about you giving skating pointers to some young ones. You sure the world's ready for Wes Hunter, youth mentor?"

I felt as transparent as sea glass under her gaze. Small towns didn't need internet—they had gossip networks, and this one spanned the twenty miles between Whistleport and Ironhook.

I hefted my bag higher on my shoulder. "Kid had a grip problem. Figured he should know before he developed bad habits."

"Course you did. Nothing wrong with remembering what you're good at."

Eric's grin widened. He was enjoying our conversation entirely too much.

She straightened, reached into her jacket pocket, and pulled out a paper sack folded neatly at the top. "This is your usual from the co-op. Thought I'd bring it to you when I heard you were on your way back."

The sack was warm against my palms, heavier than expected. "Thanks."

"Island folks take care of their own. Always have."